Let’s face it. We’re oversaturated with visuals that are all style and no substance. In the era of ever-increasing visual content, capturing images that not only look pretty but also convey profound narratives is essential. Documentary photography serves as an exceptional medium of storytelling that goes beyond the constraints of mere image capturing. Furthermore, this art form also allows you to reveal truths, tell tales, and evoke emotions, transforming the viewers’ perspective. In this article, we’ll dive deep into using documentary photography to tell authentic stories through images.

What Is Documentary Photography, and Who Does It Serve?

So, what is documentary-style photography? In short, documentary photography primarily chronicles significant and historical events. It typically exists in professional photojournalism or reportage, but it may also be an amateur, artistic, or academic pursuit.

Here are some examples of documentary photography goals:

Historical Documentation: Documentary photography records historical events, societal changes, and everyday life. Because they capture moments in time, documentary photos help us understand the context, people, and impact of past events.

Social Commentary: Many documentary photographers aim to start conversations about societal issues. They do this by presenting viewers with images that depict realities that may be ignored or overlooked. For example, a photo series on homelessness might shed light on the severity of the problem in a particular city or country.

To Inform and Educate: Documentary photography can play a vital role in educating the public about events, issues, or topics. Through visual imagery, photographers can convey complex issues in an easily understandable and impactful way.

Advocacy and Raising Awareness: Documentary photography can also advocate for change or raise awareness about a particular issue. For example, images depicting the impacts of climate change or the effects of war can drive people to action.

To Humanize: Documentary photographers often aim to humanize their subjects, especially in cases where they are part of marginalized or misrepresented groups. As a result, photographers give a voice to these individuals, allowing viewers to empathize and better understand their experiences.

Artistic Expression: Even though documentary-style photography focuses on representing reality, it doesn’t mean it can’t be creative. In fact, many documentary photographers have cultivated their own unique styles and perspectives. Incorporating creativity into their work elevates their images beyond simple documentation into the realm of art.

A History of Documentary Photography

From the 18th-Century Until Now

The history of Documentary Photography started with Social Documentary Photography, a form of photography that uses visual storytelling to highlight societal issues. An iconic example of this genre is Lewis Hine’s 1911 image “Breaker boys sort coal in at an anthracite coal breaker near South Pittston, Pennsylvania.” Hine’s photographs were instrumental in promoting social reform, such as the 1916 Keating-Owen Act that addressed child labor.

During the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, Social Documentary Photography expanded its reach. Famous documentary photography from photographers Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans depicted the struggles of impoverished Americans. These images created a powerful archive of rural poverty. This trend even brought about new sub-genres, such as the “Madonna and Child” trope, symbolizing the plight of poor mothers.

Conservation Photography

Next comes Conservation Photography, tracing its roots back to the 1860s in the U.S. This type employs a documentary style to capture nature and landscapes to promote their preservation. Key contributors include Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan, whose images highlighted the beauty of Yosemite and Western landscapes..

Furthermore, through their painterly and photographic work, Thomas Moran and William H. Jackson enhanced public awareness about Yellowstone National Park.

In the 20th century, Conservation Photography experienced a resurgence with notable contributions from Ansel Adams, whose stunning images of Yosemite influenced the wilderness movement. The discipline continues to evolve in the 21st century, reflecting global environmental concerns.

Photo Essays

Popularized by magazines like Life and Look in the 1930s, photo essays combined narrative photography and written storytelling, often focusing on societal issues. Notable practitioners like Walker Evans set the genre’s standards.

Post WWII, photographers like Robert Frank and W. Eugene Smith pushed against the genre’s constraints, leading to an evolution towards documentary work, epitomized by Smith’s famous documentary photography images of Minamata in Japan.

The rise of television as a documentary medium and the closure of crucial magazines prompted a shift towards book publishing and gallery exhibitions by the 1970s, with photo essays often featured in art gallery settings.

Social Landscape Photography

“New Documents,” also known as “Social Landscape” photography, originated in 1967 as a reinterpretation of Documentary Photography, emphasizing the exploration of life as it is. Today, it is very similar to Street Documentary Photography. Led by photographers like Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, and Lee Friedlander, this genre celebrated societal imperfections, presenting raw, often disquieting depictions of everyday reality.

These photographers used personal influence and self-awareness, shifting from the traditional objective lens of Social Documentary to a more introspective viewpoint. Notable trends in this movement included focusing on sequential imagery in photographic books and incorporating new subjects, such as suburban landscapes and color documentaries.

Ethnographic Photography

The Ethnographic Photography genre, evolving from early Documentary Photography, captures cultures worldwide, becoming a photographic tourism in the 19th century. Pioneers like John Beasley Green, who documented Egyptian ruins, made it a credible scientific record.

The genre was institutionalized through platforms like National Geographic Magazine, formerly a scholarly journal. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) and the British Mass Observation Project further strengthened this style, focusing on societal issues and public sentiments.

In the 1960s, art theorist Hal Foster observed the shift of art toward visual ethnography with trends like Performance Art blurring artist-audience boundaries. Works like Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave (2001) exemplify this, showcasing how artists recover suppressed communal histories.

War Documentary Photography

The War Documentary Photography genre, originating with John McCosh’s images of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1848, captures the grim reality of war. Early photographers like McCosh and Roger Fenton, the first Official War Photographer, focused on static scenes due to technological limitations.

Matthew Brady’s work during the American Civil War, particularly his “The Dead of Antietam” exhibit, brought war’s brutality to the public eye.

Technological advancements in the 20th century allowed soldiers to carry cameras, leading to raw and unfiltered images from World War I.

The handheld Leica 35mm camera’s invention in 1925 brought War Documentary Photography closer to Photojournalism, with notable figures like Robert Capa capturing iconic war images for mainstream publications.

One of my favorite war photographers is the American photojournalist James Nachtwey, who witnessed some of the most brutal and significant moments of history since the late 20th century. His book, “Inferno,” is a chilling documentation of wars and conflicts from around the globe.

Documentary Films

The documentary film is a genre believed to be defined by Boleslaw Matuszewski in 1898; it initially developed with travelogue and city symphony films in the early 20th century, presenting scenic views and non-narrative structures, like the 1921 film ‘Manhatta.’

Avant-garde influence, like in Luis Buñuel’s 1933 film ‘Las Hurdes: Tierra sin Pan,’ persisted alongside feature-length documentaries, such as the successful ‘Nanook of the North,’ despite its authenticity controversy due to staged scenes.

By the 1930s, the genre evolved into political and propaganda films with an ideological bent. Social documentaries promoted political reform, like ‘Misère au Borinage’ in 1934, while government-backed propaganda films, such as Leni Riefenstahl’s ‘Triumph of the Will,’ championed specific ideologies, notably Nazi beliefs in the 1930s.

Documentary Realism, a post-WWII Italian film style, focused on the everyday lives of regular people in post-war or Nazi-occupied Italy. To this end, it used improvisation and nonprofessional actors for an authentic feel. You can find it showcased in films like Rossellini’s Rome and De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves.

Influenced by the ideas of French critic André Bazin, who favored unobtrusive filmmaking, the Cinéma Vérité movement emerged in France. Led by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, it aimed for pure realism, with Chronicle of a Summer serving as a critical example.

In Britain, the Free Cinema movement emphasized filmmaking free from commercial and propagandist influence. In short, it concentrated on the lives of the working class. Using handheld cameras and non-linear narration, they created inexpensive documentaries on 16mm black and white film stock.

Example: Lindsay Anderson’s O Dreamland

Documentary Photography Now

Facing challenges from television media and the rise of postmodernism in the 1970s, Documentary Photography evolved to incorporate a critique of authorship, cultural bias, and appropriation. Adopting a postmodern lens, photographers began to explore marginalized communities and cultures, often from an ethnographic perspective.

Some documentary photography examples include:

- Don McCullin’s urban strife depictions

- Manuel Rivera Ortiz’s portrayal of rural village life

- John Ranard’s work on the boxing world and Russian prisons

- Sebastião Salgado’s studies on global labor and migration

- Graciela Iturbide’s immersion in indigenous Mexican communities

How to Do Documentary Photography?

Before diving into Documentary photography, you first must master the basics of ISO, aperture, and shutter speed. Beyond the technical aspect, this type of photography is centered around storytelling, perhaps more so than other niches.

As a documentary photographer, you’re not just a silent observer but an active participant. You will immerse yourself into the milieu you’re documenting. To truly master this craft, there are some documentary photography ideas and key points to remember.

[Related Reading: Documentary Photography: Adding Family Photojournalism Sessions To Your Portrait Business]

Research Is Key

Research is the lifeblood of a documentary photographer. With this in mind, get to know the stories, the people, and the environment before photographing them. As a result, actual authentic images will emerge from the depth of understanding.

Pro Tip

Don’t limit your research to conventional sources. Intelligent researchers know to tap into varied resources. Use online forums, social media trends, podcasts, or even local community meetings to gain a comprehensive understanding of your subject. This can also help reveal unconventional narratives and perspectives, providing a richer context for your work.

Create Connections

Documentary photography thrives on establishing genuine connections with your subjects. Let them feel your presence and get comfortable around your camera. In time, they’ll serve you raw, unfiltered moments on a silver platter.

Pro Tips

These tips may sound like they’re canceling each other, but they’re actually both important. In time, you’ll learn to master them both simultaneously.

- Learn the art of blending into the environment. Your presence should not alter the behavior or routine of your subjects. Respect the personal space of your subjects, so you can capture life as it naturally unfolds.

- Don’t just be a visitor, be a participant. Spend days, weeks, or even months immersing yourself in the lives of your subjects. Additionally, share meals with them, join their celebrations or their mundane daily activities. This immersive experience will provide a depth to your photos that can’t be achieved with a casual visit. As a result, your chances increase for creating profound narratives instead of just snapshots.

Patience Is a Virtue

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither is a powerful photograph. Patience is your best friend when it comes to capturing those blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments. From time to time, you might need to wait hours, days, or months to capture the perfect shot. As Henri Cartier Bresson would put it, you need to find “The decisive moment.”

Ethical Considerations for Documentary Photography: The Fine Line

This is an important point! Remember, as a documentary photographer, it’s your responsibility to respect the dignity and privacy of your subjects. Abiding by ethical guidelines ensures the integrity of your work while demonstrating respect for the communities and individuals you’re portraying.

But how can you do that? What rules do you have to follow? Here are some critical guidelines:

Informed Consent

Always get permission from your subjects before you photograph them, especially if you intend to publish or distribute the photographs in any way. Subjects should understand how and where their image will be used.

To simplify this, you can create a consent form. In this form, include the project and expected photograph usage – social media, magazines, etc. Also, include a section mentioning the subject’s rights to withdraw from the project at any point.

Before publication, show your subjects the photographs taken to confirm if they are content with their use as outlined in the informed consent document – to avoid potential disputes after publication.

Respecting Privacy

Sometimes, it can prove difficult to balance the ethics with your ability to tell the story in an engaging way. This holds especially true when you want to tell the story precisely to make a difference. In this situation, it’s hard to dismiss the ethics.

Above all, it’s crucial to respect people’s privacy and not to photograph in places where individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy. Photographers should always respect the personal space and limits that the people they are taking pictures of. Hold to this even if these limits stop you from telling the story you want.

If you’re unsure, always ask the person for permission to take and use their photos. The most essential thing is that you make the people you’re photographing feel comfortable. Make them trust you. So, be honest about your intentions and your role.

Building Trust and Protecting Your Subjects

Consider the potential harm your photographs might cause to your subjects, whether it’s embarrassment, stigmatization, or even physical danger. Always prioritize your subjects’ well-being above getting the perfect shot.

Truth and Accuracy

Documentary photography is often seen as a form of visual journalism. Because of this, you should strive to depict situations as accurately and truthfully as possible. Do not manipulate images in a way that alters the reality or context of the scene.

Critics argue that digital editing practices compromise the integrity of the images and the photographer’s role as a reliable observer of events. For the preservation of ethical standards in documentary photography, it’s crucial that photographers remain transparent about their photo manipulation.

Documenting Vulnerable Populations and Individuals

The terrain of documentary photography often brings photographers face to face with vulnerable groups and individuals, such as the homeless, refugees, or impoverished populations. Appropriately photographing these populations necessitates respect for their dignity and sensitivity to their circumstances.

Biases can unintentionally skew the representation of the subjects being photographed. In turn, this often leads to a false or oversimplified portrayal. This can occur due to a lack of understanding of the cultural nuances, preconceived notions about a certain group of people, or personal beliefs.

Always strive to understand and respect the cultures and customs of the people you photograph. This can help prevent offensive or harmful misrepresentations and aid in portraying your subjects faithfully. Introspectively acknowledge your biases and actively strive to counter them.

Exploitation in this context can manifest in many ways: sensationalism, dehumanization, intrusion, or voyeurism. To avoid this, photographers should avoid reducing their subjects to mere objects of pity, fascination, or scorn. Instead, their work should aim to humanize, to enlighten, and to provoke thoughtful conversation.

Technology Infringing on Privacy

Technology like geotagging, which records location data in image files, is a beneficial tool for photographers to manage their photo collections. However, if not used cautiously, it could expose sensitive information, like the home addresses of vulnerable subjects, to individuals with malicious intentions.

Furthermore, certain editing software use facial recognition to identify people in photos, which can pose severe privacy threats.

Credit and Recognition

Provide appropriate credit to the individuals, groups, or communities featured in the photographs. This means recognizing their contributions in the context of the story being told, and if applicable, naming them in photo credits. Their stories form the backbone of the work, and it’s only fair and ethical that they’re acknowledged for it.

Pro Tip

If you want to get deep into the topic, listen to this insightful talk about ethics in documentary photography between photographers Sarah Waiswa, Liz Hingley, and Savannah Dodd.

Crafting Your Visual Story via Sequencing

Sequencing is essentially the art of arranging the puzzle pieces. Each one is vital, but the true magic happens when they all fit together, creating a story greater than the sum of its parts. Paul Taggart has an excellent course on this that takes you step-by-step into making your own photo essay.

Here’s a summary of the key factors that are important when composing your story:

Identify Your Narrative Arc

Just like a good book or movie, a visual story should have a beginning, middle, and end. This gives it structure and helps guide the viewer. As an example, the opening could introduce the main characters or the setting. Then, the middle might be the unfolding of the main event or the escalation of the conflict. Finally, the end should tie up loose ends and leave the viewer with a clear sense of closure.

Visual Variety

Using a variety of shot types – wide, medium, and closeup – will provide different perspectives to engage the viewer. Wide images set the scene, medium shots give it context, and close-ups provide intimate details. Mix these shot types to maintain the viewer’s interest and offer a comprehensive sense of the story.

The Power of Juxtaposition

The way we position images next to each other can create new meanings that weren’t present in the individual photos. For instance, consider a picture of a wealthy person dining in luxury placed next to a picture of a homeless person searching for food. This juxtaposed layout creates a powerful commentary on social inequality.

Use of Color and Light

Color and light can create mood, evoke specific emotions, and highlight essential elements of your story. For example, warm colors might suggest joy, passion, or lightness, while cool colors can evoke sadness or tranquility. Shadows and contrasts in lighting can heighten drama and suspense.

Continuity and Transitions

Ensure there is a visual continuity between your images. For instance, this could be through using similar colors, themes, or subjects. Also, consider including transitions between shots. An abrupt transition might create shock or surprise, while a smooth transition can maintain a serene, flowing narrative.

Reflect and Refine

After your initial sequencing, take a step back. Look at your story as a whole. Does it flow? Is there a straightforward narrative? Are there any images that disrupt the flow or seem out of place? This reflection is crucial for refining your story and making it more effective.

Other courses on Documentary Photography and Photojournalism:

- Documentary photography projects by Marcos Zegers, Photographer

- Introduction to Visual Journalism by Gladys Serrano, Documentary Photographer, and Videographer

- Introduction to Photojournalism: Capture Powerful Stories by Finbarr O’Reilly, Photojournalist

- Photo Essay: Telling a Family Story (a course on documentary family photography) by Paul Taggart, Photojournalist

Wrapping Up

Creating compelling visual stories through documentary photography demands skill, patience, empathy, and ethical sensitivity. As Magnum Photos co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson once said, “Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.”

The best documentary photography is about finding and sharing the unseen, the unheard, and the unfelt aspects of human existence. When doing a documentary account of something, ask yourself, does your narrative evoke the emotions you intended? Furthermore, does it accurately represent the story you wish to tell?

To further enhance your technical skills and actually focus on the story in front of you, consider exploring additional resources and tutorials offered by OhMyCamera.

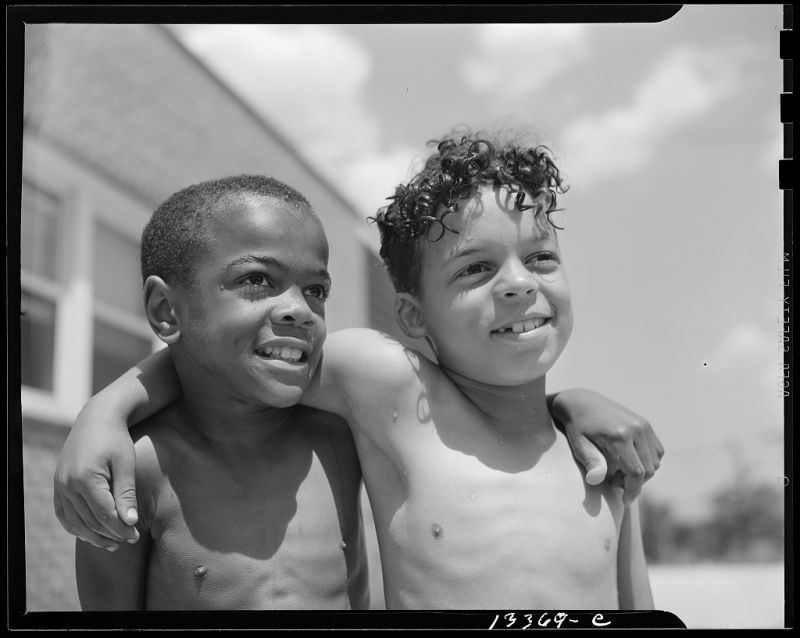

**Feature image, “Children in Seville, Spain,” by Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Get Connected!