Have you been thinking about getting a drone to help elevate your photography business? I’ve spoken with lots of photographers who are considering adding a drone to their tool set so it’s probably a safe bet that you’ve at least thought about the possibility. I am one of them… I have 2 drones and I recently acquired my part 107 FAA license (which is a commercial drone operator license). This article is based on my experience of going through the process and I have included some insider information on actually getting the license and also given some “in the field” encounters and thoughts on why doing this the right (and legal) way will really help determine the future of drone photography for small businesses.

What is considered a drone?

So what is a drone really? The FAA defines a drone (or a sUAS – small Unmanned Aircraft System) as an aircraft that has no possibility of human intervention directly from the aircraft and weighs more than 0.55 lbs but less than 55 lbs at takeoff. The sUAS’s you would use for photography are NOT toys. These are precision engineered machines that are loaded with electronics, distance sensors, GPS monitors, live video feeds and give the ability to take some AMAZING photos & video from vantages previously only accessible via helicopter and even some that weren’t. They have the ability to fly far out of sight (3 miles away or more, automatically hover in place even with moderate winds, go over 1600’ above ground level (AGL), can travel over 60mph and have at least 4 blades that are rotating at 7,000rpm or higher (which can shred fruits & vegetables, even at “idle” speeds).

The FAA has authority over ALL airspace in the US. This means as soon as you leave the ground, then you must follow the FAA rules governing safe flight. It doesn’t matter if you are in your backyard, at a park designed for UAS’s or near an airport. The FAA has so far been, in my opinion, ill-prepared to handle the sudden popularity of drones in the US but has put guidelines in place for both hobby and commercial pilots. I expect them to continue to add rules and regulations and truly hope that they streamline the information that is out there as there is still a lot of confusion.

Commercial or recreational?

First and foremost, there are LOTS of contradictions out there coming from both drone pilots and the FAA itself in regards to the guidelines. So let’s start with a few of the basic rules that are in place that you need to know if you want to use a drone for commercial photography.

- Commercial usage is very broadly defined by the FAA and isn’t “set” to the type of flight you made. For example, you take a cool photo during a recreational flight, which you later sell, then the FAA will retroactively classify your flight as commercial and all the commercial rules apply.

- If the usage of a drone directly or indirectly benefits your business, then it’s considered commercial usage. For example: Placing a video on youtube where collect ad revenue from, a farmer using a drone to survey his crops to check for drought or disease or a neighbor giving you $50 after checking their gutters – all considered commercial usage.

- Flying at night is not allowed without a waiver.

- Flying directly over people not directly involved in the production is not allowed without a waiver.

- You must fly within VLOS (Visual Line of Sight) at all times.

- Interfering with manned aircraft is prohibited and will make you famous in all the wrong ways.

- Commercial operators must understand the airspace classification they are in and get appropriate permissions if needed.

- 107 operators do NOT have to contact airports within 5 miles to notify of your operation. They must, however, know what airspace they are wanting to operate in and acquire any COA’s (Certificate of Authorization) before operating there.

Basically, If you stand to commercially benefit whatsoever from your drone, then the FAA requires you have your license. With a part 107 license, you have the ability to apply for waivers and authorizations for numerous restrictions such as operating in certain airspace, flying at night, over people and others. To get a waiver or authorization (they are 2 different things) you must be able to explain, in detail, how you will safely operate your aircraft while operating under those conditions.

Do I need to register my drone?

This has been very hot topic lately. As of this writing, maybe. In Taylor vs FAA, the courts found the FAA did NOT have the legal standing to require recreational operators to register their drones with the FAA. However, they do encourage you to do so and, remember, the FAA definition of “commercial” is very broad. So if you are using a drone commercially, even part of the time, then you have to register it regardless.

You can register it yourself here: https://registermyuas.faa.gov (there are companies which offer to do it for you – for more money of course. Don’t do it, it only take 4-5 minutes and is super easy).

If you have a drone you fly both recreationally and commercially, you need to register it as a commercial drone. You do NOT need your airmen’s certificate to register it as commercial.

What’s the big deal if I fly without a license for commercial work?

I was recently shooting a wedding with a videographer who also had a drone. I exchanged some chit chat with him and asked if he had called the airport before flying because I was getting ready to fly mine. His response was “what airport?”. I think my eyebrows went thru my forehead. There was a small airstrip on the backside of the venue (less than 1/4 mile away) and the airstrip orientation was facing our exact location. Any drone flight over 100’ could have seriously impacted a taking off or landing plane. Having the knowledge of how to read sectional maps would have told him that but, without any formal training, he didn’t even know how to check).

The same videographer also had the groomsmen shooting nerf darts AT the aircraft that was going straight towards them. We later found one of the nerf darts had been cleanly sliced in half by one of the blades. Without going into full rage mode, I just want to say what a terrible, terrible idea this was. Drones are not toys and will lacerate skin very, very easily. No one wants to send the bride, groom, bridal party or innocent bystander to the emergency room because you “wanted a shot”. Just because you don’t need a license to buy one doesn’t mean you should be immune to learning about the safety factors and potential hazards of what an out of control drone can do. Just Google “drone injuries” on youtube and you’ll get the drift about how quickly things can go bad. Don’t get me wrong, this was a cool shot but there is very much a risk vs. reward ideology that is talked about at length when you’re studying for your license.

There have been numerous news stories about drones hitting people, causing mild to severe injuries, interfering with aircraft operations and even being shot down by people who don’t like them. Believe it or not, I couldn’t find ANY stories where someone who shot a drone down, even when it wasn’t over their property, was met with any criminal charges. In other words, it’s still the wild west out there so understanding the law, following the rules and being prepared is of paramount importance. Getting educated and getting a license goes a very long way to achieving that goal.

So getting educated is really the key here. Again, these are not toy airplanes. They can cause serious damage to property and people. Operating safely and legally will go a very long way to protect you personally, and your business, from any liabilities.

How do I get my license?

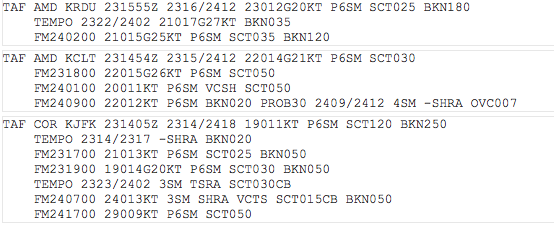

How hard is it to get a license? Well, I had no previous experience in the aeronautical field so, from that perspective, it’s definitely achievable by anyone. It’s just not something you can decide you want to do today then pass a test tomorrow. You have to study and understand a whole different type of aviation language, maps, and acronyms as well as understanding the aeronautical “sectional” maps and airspace classifications. You’ll also have to learn how to read METAR’s (weather reports that look like computer code), TAF’s (aviation weather forecasts) basic airport operations, NOTAM’s (Notice to all airmen), basic meteorology, flight physics and a few other things.

Here are a couple of examples of what you’ll have to learn about:

What’s the class C shelf floor of KRDU?

What is the current visibility at the Raleigh airport? (This is a METAR)

When are scattered thunderstorms expected at JFK? (This is a TAF)

When is the RDU airport closing runways and how could that impact your flight operations if you are operating near the airport? (This is a NOTAM)

To be honest, when I first started to study, I thought most of the information was useless because FAA just threw a test together to cover their bases. However, as I went thru the material, it became apparent to be a safe pilot, you need to know all of these things, not to mention they take you hanging an 8lb weight 400’ over over someone’s head with whirling blades very seriously. In addition, the sky has no highway signs so you need to be able to understand where and when you can fly safely and when you shouldn’t.

Please don’t let the above study material scare you. It’s very logical information but because we fly everything from hot air balloons to planes without GPS to the newest fighter planes and even the space shuttle in the same airspace, the weather, NOTAM, TFR and other information must be able to be received and read by all types of people and equipment, it’s presented in a very analog fashion. There are tons of tools which will help you study but once you get it, it’s pretty easy to decipher.

The FAA has a study guide and there many other resources have gobs of freely available information on the course material online. There are also numerous “boot camp” classes available online so if you prefer a more structured learning environment (as I do), that may be the better option. I personally used www.remotepilot101.com for my studies but, again, there are tons of companies out there all providing roughly the same service. Expect to spend $150 – $200 on classes like this but an added benefit is they typically also are there to answer questions on anything that is confusing.

Prepare to spend anywhere from 30-40 hours reading over the material, taking prep exams and looking up questions you have. All the information is out there, just make sure you source it from the FAA and not some Facebook group because, well, it’s Facebook.

Taking the test

To get your sUAS license, or Part 107 license, you must pass a written test at an accepted FAA testing center (which is $150). You want to be overly prepared when you go into this test as you are not allowed to bring anything in but what they provide you. Scratch paper, a pilot supplement and a couple of pencils. The test is designed to trick and mislead you so you definitely want to be well-prepared before taking it.

I passed the test, now what?

So after taking the test (and hopefully passing), it will take up to 48 hours for the testing center to submit the information to IACRA. Once they have it you can register your information, associate it with your test score and then they will issue you a temporary airmen certificate within 2 weeks. The FAA is then sent the information and they will send you your permanent license within 2 months. The FAA requires that you keep both your FAA license and drone registrations on you at all times when operating.

While the FAA license is required, some states also have a separate license process you must follow in order to commercially operate a drone in that state. The content of those tests follow the FAA regulations for the most part, but there may be some additional state laws you need to be aware of. In my experience, I read the material provided once, took the test and passed so it was far easier than the FAA test.

So why is this important?

As I said above, it really is the wild west right now for drones and the laws are still changing. Being a proactive and “legal” member of the community will help us safeguard the ability to fly drones for our businesses. A very big part of this is helping to educate the general public about their use and promoting safe and responsible operations. This will go a long way in helping our cause and businesses. Anti-drone sentiments are on the rise in the general public so greeting someone watching you fly in a friendly tone, showing them the cool stuff and explaining what you are doing will go so much further than being defensive and saying “I have a right to fly”.

I certainly don’t have all the answers but have spent countless hours learning as much as I can about safely operating drones, the legality of using them and the public opinion, so if you have a question please ask! I will do my best to answer.

Get Connected!