The Easychrome is a DIY color-infrared, LO-FI point & shoot camera that emulates the look of Aerochrome Film. Much more than a mere shift in hue or a digital manipulation, the Easychrome renders reflected infrared light in sizzurp-stained shades of purple, pink and red. Here’s how to make one yourself.

Despite the metallic connotations, Aerochrome is a color-infrared film that twists reality into scenes of surreal pink landscapes and vivid magenta vistas. If you haven’t yet heard of it, consider this a friendly brainwashing… it’s one of the most psychedelic films ever made:

The artistic allure of this discontinued aerial surveillance film lies within its ability to depict the unique reflection of infrared light in confronting (and oddly beautiful) tones of red, pink and magenta. By rendering reality (as we can and cannot see it) in a false color scheme, it becomes possible to discriminate with exceptional clarity the smallest of details previously indiscernible to the human eye.

A soldier in lizard camouflage perched in an eastern Congo jungle might not be easy pick out with a pair of eyes, but the the various shades of dye used in their clothing (As so to mimic the appearance of vegetation in visible light) will now stand out prominently against the blood-red reflections of infrared light from vegetation when rendered with Aerochrome film:

Plants, ONLY requiring energy in the spectrum of visible light to carry out the vital process of photosynthesis, reflect almost all light in the near-infrared spectrum from their chlorophyll containing leaves and flowers.

The name ‘Easychrome’ is an portmanteau of Easyshare, the camera in-question that will be hacked to see in full spectrum (infrared & visible light) and Kodak Aerochrome film – You heard it here first! Aerochrome is notoriously difficult to use, requiring constant refrigeration and special filters, hence the name Easychrome also refers to the ease of obtaining an Aerochrome-esque picture thanks to the simplified controls of a point & shoot camera.

[REWIND: See the ‘World In Infrared’ With Your Own DIY Conversion]

All You Need Is:

- An old point & shoot camera. You or someone you know is bound to have an old camera lying around collecting dust that can be artfully obtained ;)

- Yellow filter. i.e. yellow cellophane, protective glasses, lolly wrapper or anything that turns the world yellow when you look through it.

- Various tools: Screwdriver, Pliers, Knife, Tape etc…

Note: This is a guide specific to a Kodak Easyshare M1063 10.3 megapixel camera. However, most point & shoots are built to more or less the same specifications, so you can use the same principles, concepts and (in a lot of cases) the same steps found in this article if you don’t have an Easyshare.

Random Disclaimer: The blinding white light that scores your retina during a photo is most likely produced from a high voltage flash tube. When you hit that shutter with the flash on, a burst of voltage (anywhere between 2000 – 150,000 volts) is sent to ionize a gas (such as xenon) in a glass capsule to produce a bright flash of light. As such, almost every camera with a built-in flash these days is home to a fully-charged, high-voltage capacitor even if the camera is dead or without batteries. If you touch the wrong terminals, that burst of voltage might discharge into you or your once-functioning camera. We’re dealing with heart-stopping voltages here and there are safe ways to discharge a capacitor, however, this is not an electronics tutorial. If you happen to ruin your camera during this process, please send all complaints/photos to the World In Infrared Facebook page, I shall make obituaries in their honor…

Without further adieu, let us convert this POS, bland and dated Kodak Easyshare camera into a full-spectrum seeing, Aerochrome-emulating, jury-rig point & shoot!

Step 1:

Search for any screws on the outside of the case. There are a total of 5 on this camera: 2 on the left-hand side panel (when holding camera in photo-taking position); 1 on the right-hand side panel; 2 on the bottom panel.

Screws are often hidden beneath things like rubber feet and just inside the hinges of battery compartments it would seem…

I have to put the screwdriver in at an angle to reach this one. It’s important to remove all the screws holding the casing in place because we don’t want to break anything when separating the front and back plates.

Step 2:

It’s amazing when a completely unrelated skill you have previously learned emerges from the past to help you out with a new skill you are learning now. Surely, if not for my formative years perched behind a fretboard in a sweaty underground band rehearsal dungeon with 3 of the most dubious cats you’ll ever meet, I wouldn’t have reached for my guitar pick to ‘serenade’ the 2 halves apart, closing my eyes and proceed to play a melody that could part the red sea like Moses:

Be mindful of any awkward application of force when you are trying to pull apart such delicate device. The 2 halves may feel stuck, and your instinct is to apply an overabundance of force. Should the 2 pieces suddenly budge, you wouldn’t want the delicate ribbon cables connecting things like the LCD screen to the motherboard to get ripped from their sockets like supple teeth tied to a doorknob with string.

Where to now? The sensor is almost always (in my experience at least) accessed through the back of the camera, rather than from the front (beneath the lens). On a point & shoot, this never seems to be too far beneath the LCD screen

Step 3:

“Damn Kodak, did you enjoy the fish & chips?” exclaims my brother Ryan (Happy Birthday BTW – Jan 1st) while snickering over my shoulder. Gently lifting the LCD screen up and out (still attached by a flex cable), it reveals a metal plate complete with 2 of the greasiest fingerprints he could ever imagine inside a gadget. Now it’s time to leave my own.

If you look closely, the cable is held in place on the motherboard by a locking latch on the connector. To release the lock, simply slip your fingernail beneath the latch and ‘snap’ it upwards. Don’t worry about breaking anything, the latch is attached by a hinge. Once open, the cable (and attached LCD screen) should slide out:

Step 4:

The keypad is released the same way. The cable on this Kodak Easyshare’s keypad doesn’t even have a cable lock, it just slides out of the socket. The keypad was, however, stuck on the metal plate with some type of adhesive. Knowing the properties of a flexible printed circuit meant I could peel it of like a sticker with no damage at all!

Step 5:

Now that the LCD screen and keypad have been removed from the camera, the next obstacle is the metal plate that just housed them. It is held onto (what’s left of) the camera body with tabs and clips. I use a flathead screwdriver to pop the metal arms off each plastic tab (found on all sides of the camera) until the plate lifts off with no pressure at all.

Permanent market and flexible printed circuitry mark the spot: See that large rectangular orange flex cable coming off the green motherboard (Right panel)? That’s the backend of the sensor. I pick it up to look closer and…

FC|àïüK²)9>A\…er!⏚ The capacitor got me! That’s what a few thousand volts to the fingertip looks like… Nerves are scrambled… Heart rate surely over 200bpm… Camera flung across the table and into the wall… I reconnect the screen and keypad… Switch it on to see if it still works…

I breath a sigh of relief when I see the lens elongate like Pinocchio telling his worst lie yet: It still works. However, this Kodak and I are starting to develop a love/hate relationship.

I won’t lie, this could have been prevented by following my own advice in one of the first paragraphs of this article: DISCHARGE THE CAPACITOR. Carrying out this procedure the proper (and safest) way requires specialized knowledge and tools such as electronics and a soldering iron, so if you don’t know what you are doing, the odds of permanently destroying the camera increase from here on out (As if it wasn’t already doomed from the start).

But don’t let a formality like voltage stop you from achieving success on your DIY quest! Would a doctor take off their gloves and leave a patient with their heart exposed during transplant surgery?

Remember kids, if you can’t discharge the capacitor, just recall this ancient electronics adage: ‘Keep one hand in the pocket when playing with a socket!’. By holding a high voltage device with both hands, you have created a circuit with your body (through your arms and across your chest), in which your heart is the start/lap/finish line for a reckless group of electrons to tear through. Don’t give electricity a chance.

Step 6:

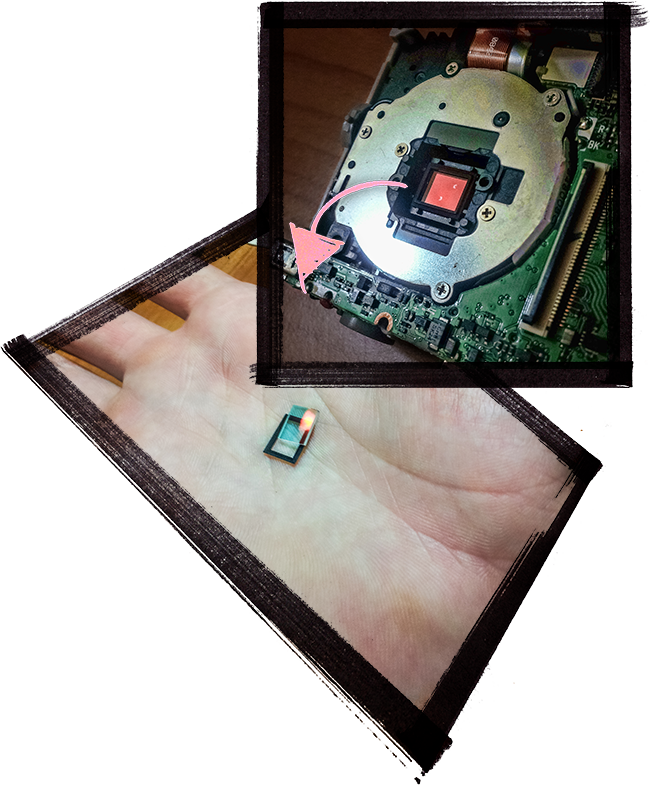

I snoop around and spot just 2 screws and a cable latch holding what I believe to be the CCD sensor chip to the camera. I remove the 2 screws (Left panels) and unclip the cable latch (Right panel; As seen in step 3).

The chip is removed gently and without effort revealing the core element of any digital camera:

Behold the 10.3 megapixel CCD sensor. While definitely not the all-seeing-eye, this tiny piece of electronics will be able to see a lot more than me. Next, we’ll enable the camera to capture that digitally.

Step 7:

With the sensor removed, we should now have access to… ahh yes, the hot mirror. This tiny piece of red/green/blue (depending on the angle) tinted glass is what we are here for. It is designed to allow the transmittance of visible light, but not infrared. Now we must remove it.

Sometimes the hot mirror is held in place with an adhesive, but this one was easy. I gave Easyshare a gentle tap and it popped out like batteries from a remote.

Step 8:

Follow this guide in reverse to reassemble the camera. If you still have a few holes that you physically could not find screws for, don’t worry! Nilesh’s 550D went back together minus one of the main body screws next to the SD card slot! He still doesn’t know…

Step 9:

Now it’s time to turn this Easyshare into an Easychrome. To do that, let’s look at how the film actually creates its colors:

Aerochrome film begins with 3 emulsion layers sensitive to the following colors: Infrared & Blue, Red & Blue, Green & Blue: [I+B,R+B,G+B].

In order to get a color balanced picture in terms of visible reality (i.e. with blue skies), a yellow filter (such as a Wratten No. 12 (minus blue)) must be used over the lens to eliminate the color blue from the scene. This limits the exposure of all 3 emulsion layers, which are ‘inherently sensitive to blue radiation’, to their ‘intended spectral region’: Infrared, Red, Green respectively: [I-B,R-B,G-B] > [I,R,G].

After the emulsion has been exposed to light (as indicated by the grey boxes in the EXPOSURE portion), the reversal processing mechanism maps the exposure of those channels to Red, Green and Blue respectively: [I-B,R-B,G-B] > [I,R,G] > [R,G,B]

In the case of exposure to infrared light, processing will produce a mix of yellow and magenta dye (as indicated by the black boxes in the bottom REVERSAL PROCESSING portion), without cyan, to form the color red.

Well this is my Wratten filter No.12: A piece of yellow cellophane. It has the same effect as a yellow filter by *cough*somewhat*cough* canceling the color blue (by cutting off light somewhere below 500nm). I call my mum as she’s on the way home and ask her to get me a packet. $2 for an amount that you could make a thousand imitation Wratten 12’s from (This is the only expense of the project so far).

When white balanced and hue corrected, the corresponding color shift renders all reflected infrared light as pink, magenta and red… Just like Aerochrome. There you have it: The Easychrome. Easy, huh?

Thanks to the cellophane, the quality of the camera becomes reminiscent of LO-FI 35mm film photography, so I felt the pictures looked best in some of my Dad’s old slide covers from the 60’s. All pictures were taken around Suva, Fiji. Enjoy!

Easychrome is the brainchild of an illicit rendezvous between the minds of Steven Saphore & Nilesh Pawar, purveyors of theWorld In Infrared.

Get Connected!