-

Term: High ISO

Description:High ISO capability refers to a camera's ability to deliver clean, as opposed to noisy, images at high ISOs. ISO is a number that represents a sensor's sensitivity to light, and while using a higher ISO brightens an image, it also diminishes images quality by introducing noise. A camera with good high ISO capability is able to use higher ISOs before image quality degrades to an unusable level.

High ISO

High ISO Technical Explanation

Digital camera sensors use pixels, or photosites, to “collect” photons of light, and thereby create an image. The entire sensor has a single “base” or optimal light sensitivity, also known as its quantum efficiency. Quantum efficiency is, in simple terms, the sensor’s efficiency at turning photons into electrons. In other words, when the pixels on a sensor are able to gather the most light they possibly can, this results in the best image quality possible for that sensor.

High ISO Performance

As light sources get dimmer, fewer photons hit each pixel. Thankfully, sensors can amplify the “image information” they do receive, thus rendering the resulting image sufficiently bright again.

Each ISO corresponds to a stop of light; ISO 100 is often where digital cameras “start”, and ISO 200 is one stop brighter, ISO 400 is another stop brighter, and then ISO 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, 12800, …and so on and so forth.

Technically however, the camera is not actually changing the sensitivity of the sensor itself. It is merely amplifying the existing signal, during the conversion process from an analog signal to a digital signal, before the image is actually created and written onto the memory card.

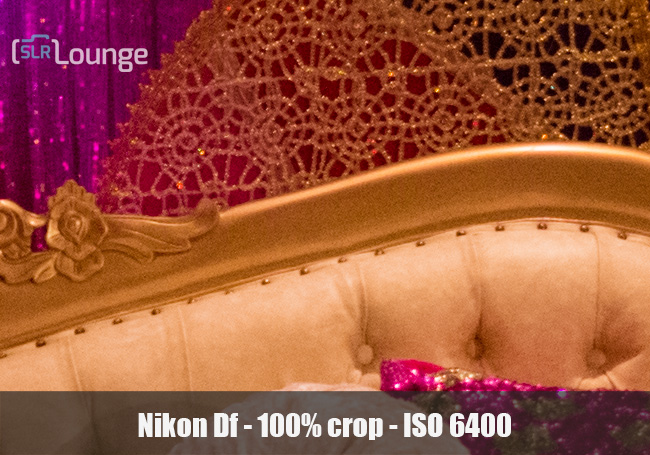

Both sensor design and the physical sensor size will affect the image quality of a sensor, especially when using a higher ISO. For each stop higher you set your ISO, a correct exposure will exhibit slightly more image noise, less sharp detail and color quality, and less overall dynamic range.

A larger sensor has an advantage, however, because each pixel is much larger and therefore collects more photons overall, both in individually and the sum total across the whole sensor. This is why a “full-frame” sensor is often preferable for photographers who highly value low-noise, high quality images even at high ISOs.

Smaller sensors, however, are also becoming highly efficient at “collecting photons”, and therefore deliver good quality images even at commonly used high ISO’s such as 1600 or 3200.

What is ISO “HI-1” or “H1”

At a certain point, a sensor’s amplification capability becomes unreliable, and cannot achieve a precise “stop” that qualifies as a certain, specific ISO. At this point, the camera lists this as “ISO HI-1”, to note that you will no longer be getting an accurate exposure. (Nor will you get very good image quality!)

Contrary to popular belief, however, “HI” ISO’s do not always denote the exact point at which a camera switches from performing its gain amplification natively, (during the analog, photons-to-electrons conversion) to “fake” digital post-production brightening. For example, a camera may switch from analog gain to digital gain for ISO’s higher than 3200, yet still list ISO 6400 before going to “HI”.

What is Dual Gain ISO?

Some of the latest digital sensors tout having what is called “dual gain ISO”. Dual gain is a technology used in sensors to change the amplification of a sensor’s image data at an earlier stage in the analog-to-digital conversion. (ADC) It is still not an actual change in the quantum efficiency of the sensor, but merely a “cleaner” way to amplify the image data, which results in a slight boost in image quality when jumping from the next-lowest ISO. On most cameras which currently offer dual gain, this happens in the vicinity of ISO 400 or 800.

This does not mean that ISO 800 is higher quality than ISO 100, rather, ISO 800 is simply higher quality than ~1 of its preceding ISO values. This technology also results in consistently better image quality at all ISO’s higher than that dual-gain switch point, compared to if that same sensor had kept using the original gain factor of its base ISO.

Reasons To Use High ISOs For Portraiture

When shooting at very high ISOs in very low light, it essentially all comes down to this: Finding a balance of image noise / detail, depth of field, and of course shutter speed related blur risks.

Using High ISO’s For Depth Of Field

Let’s say for example that you are able to shoot hand-held at ISO 200 or 400 at f/2.8. However if you have five rows of people in a crowded, dimly lit church then there is a good chance that f/2.8 will not get everybody perfectly in focus. Or your lens simply may not have sharp edges at its widest aperture, especially if it’s a faster prime or an older f/2.8 zoom. (I’ll have to write a whole different article regarding wide angle zooms and field curvature / edge sharpness!)

In this case you might want to raise your ISO so that you can hit f/4, f/5.6, or even f/8+ if necessary. Any landscape or fashion photographer may cringe at the thought of raising your ISO just to be able to shoot at f/11 hand-held, but any fellow wedding / portrait photographer will understand this dilemma.

So, pay attention to your depth of field when shooting large groups in low light, and don’t be afraid to crank your ISO up when necessary.

Using High ISO’s To Eliminate Motion Blur

The other thing portrait photographers run into is the simple fact that their subjects are moving. Even a portrait of people standing perfectly still cannot be shot at a shutter speed much longer than about 1/60 sec for very large groups, or for more artistic, creative images of a couple by themselves you might be able to pull off 1/2 or 1″ shutter speeds.

So instead of yelling at everybody in a group photo to hold perfectly still, consider raising your ISO to eliminate subject motion blur. Usually for non-squirmy adults, 1/60 or 1/100 is sufficient, or to be on the safe side maybe 1/200 sec.

Even if your subjects hold perfectly still, you still need to worry about camera shake as well. If you shoot your formal portraits from a tripod you can definitely coax a much higher keeper rate from any camera. Many portrait photographers think that using higher ISO’s (or always shooting wide open) is an excuse to never worry about using a tripod, but in my experience there are plenty of situations in which both a tripod and high ISO’s are necessary. So, just keep this in mind!

Related Articles to High ISO Definition

The Best Lens For Real Estate Photography

In this article, we’ll make sure that you understand the factors that go into choosing a lens- what focal length, zoom range, and/or aperture range is right for which situation?

Nikon Z6 II Review | A Great Camera, Perfected?

The Nikon Z6 II is a near-perfect update to an already impressive predecessor. It stacks up well against its professional competition and offers access to the incredible Z-mount lens lineup.

How To Get Started In Music Photography

Many years ago I was out with a friend at a small gig and was enjoying the music when I…

Sony A7R IV Review: More Megapixels, Better Autofocus, …Anything Else?

In this review, we’ll dive into why you may decide to stick with the A7R III, (or wait for Sony A7 IV rumors to start popping up) …OR, why you might want to consider this new megapixel champion.

Nikon D780 Review – The Best DSLR, In A Mirrorless World

Long live the optical viewfinder! The Nikon D780 is a near-perfect combination of mirrorless and DSLR technology…

What is ISO: The Ultimate Guide to Creative Use of ISO

All you need to know all in one place.

Is f/4 The New f/2.8?

I’ve noticed a trend among quite a few of my fellow photographers of switching out their flagship f/2.8 zoom lenses and replacing them with smaller, lighter, and more inexpensive f/4 zooms.

Panasonic GH4: First Impression and High ISO GH3 Comparison

I recently had a chance to use the Panasonic GH4 for about an hour and from my first impression as a GH3 user, Panasonic may have a real winner here. We will cover the video more extensively when we get a review unit for an extended period of time, but in the meantime, here are some takeaways.

Get Connected!